By: Dr Jane Williams

|

|

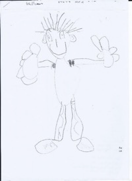

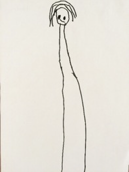

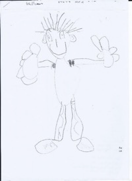

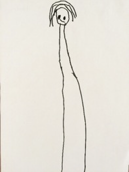

| Drawing A | Drawing B |

This is an article about the importance of active movement. So why are there children’s drawings here? As adults we are constantly encouraged by governments and health professionals to get active in order to improve our health, reduce weight and enhance emotional wellbeing. Children are encouraged in the same way. However, there is an underlying assumption that children will naturally experience active movement opportunities, after all who is not exhausted by the endless energy of 2- and 3-year-olds? But active movement opportunities involve more than just general play opportunities. Still wondering about the drawings? Let me explain.

To think and learn well, a child’s brain needs specific movement activities that drive the development of attention, balance and coordination, the foundational physical skills for learning. Brain evolution has this process sorted. All we need to do it provide the right environment at the right time. That means lots of active movement opportunities that help children move through the step-by-step pattern of motor skill development from birth. It’s not something that ‘just happens’ without the correct environmental stimulation and lots of opportunities to practise. Young children who vegetate in front of a screen miss key opportunities to be actively practising these skills and the brain and body misses out on the kind of stimulation it needs for optimal development.

In my own research involving 400 Australian Primary school students[i], teachers found that children who engaged in a daily active motor skill program, improved their physical coordination and motor control skills, as well as concentration, attention span, writing skills and enthusiasm for learning. They were also happier, more confident and coped with change more readily. In this study we tested the developmental age of children (aged 4-8 years) before they undertook a daily 30-minute program of movement challenges for 4 school terms (10 months). We found many children were developmentally immature at the first test. We then retested them at the end of the year and found that the developmental age of the children participating in the movement program increased by an average of nearly two years in the 10-month testing period. In comparison, the group who did normal classes, rather than the movement program, improved their average developmental age by only six to ten months over the same time period.

Can you tell the age of each child from these drawings?

|

|

| Drawing C | Drawing D |

|

|

| Drawing E | Drawing F |

These drawings are examples from the assessment we did to measure a child’s developmental age. We chose this test as it was fun and easy to do and teachers found it easy to implement in a classroom. It is called the ‘Draw-a-Person’[ii] test. Children were asked to draw the very best drawing of themselves that they could, both before and after the movement program. The children’s illustrations were then scored against a checklist of criteria, categories and items. Scores were ranked according to the results of peers of the same age. A child’s drawing of themselves is inciteful for researchers, teachers and parents alike. When a child can draw all their body parts, it is a visible sign that they have an internal, automatic awareness of self. This signifies a level of brain maturation necessary for the complex thinking tasks required for learning at school.

| Drawing A: William | Drawing B: William (10 months later) |

|

|

| Actual age 5 yrs, 9 mths Developmental Age: less than 5 years |

Actual Age: 6 yrs 6 mths Developmental Age: 8 yrs 3 mths |

| Drawing C: Cory | Drawing D: Cory (10 months later) |

|

|

| Actual Age 3 years 9 months Developmental Age: 3 yrs 6 mths |

Actual Age: 4 yrs 5 mths Developmental Age: 6 yr 2 mth |

| Drawing E: Annie | Drawing F: Annie (8 months later) |

|

|

| Actual Age: 4 yr 0 mths Neurological Age: 4 yr |

Actual Age: 4 yr 8 mths Developmental Age: 6 yr 8 mths |

You can see the enormous gains made in the children’s ability to draw themselves more completely, even children who were drawing age-appropriate drawings of self, benefit from the motor-based activity sessions, as their self-awareness and accompanying brain development leaps over and above what is expected for their age. Alongside teachers reports, we know these same children improved in many classroom and learning skills.

So, why wait until children are at school before making sure children’s brains and bodies are ready for learning? To find the best activities that build learning for life, dip into ‘Grandparenting Grandchildren’[iii], a book written for both parents and grandparents that will help you understand the ‘why, what and how’ of activities for the Under 5’s that not only have serious purpose but are fun and rewarding for everyone.

[i] Williams, J. (2015). Does a neurodevelopmental program affect Australian school children’s academic performance? Journal of Child Health Care, 8(1) 34-36.

[ii] Naglieri, J.A. 1988, DAP Draw a Person. A quantitative scoring system, Pearson, San Antonia.

[iii] Williams, J. & Grigg, T.A. (2021) Grandparenting grandchildren, Exisle Publishing, Chatswood, NSW. ISBN 978-1925820-79-9